Pulling the trigger: how to time an exit

Choosing the right investments for a portfolio is obviously crucial – but knowing when to exit a position is just as important. We analysed thousands of ‘sell’ decisions and found that most ended up containing losses, as opposed to securing profits. Our findings also revealed how significant delays in pulling the trigger on positions adversely affected fund manager performance.

In this article, we explore the importance of exit strategies, the approaches of different investor types, and how sell decisions are influenced by behavioural bias.

Main takeaways

Sell to cut losses: Although exiting can lock in gains, most sell decisions are made to contain losses—highlighting their primary function as risk control.

Delayed departure: Many fund managers wait too long between recognising a position is no longer working and selling. This can lead to escalating losses.

Mistimed profits: Even when exiting winners, managers sometimes give back more than 50% of peak gains before selling. This suggests consistent challenges in exit timing.

Biases shape behaviours: Overconfidence, the disposition effect, and anchoring are among the biases that can affect returns.

De-risking influence: Positions preceded by a scale-down call are exited three times faster, suggesting staged exits can prepare managers to act more decisively.

Structure improves outcomes: Managers with clear exit strategies are better equipped to act consistently and optimise outcomes.

The importance of exit strategies

There are a number of reasons why having a disciplined exit strategy makes sense when it comes to the management of investment portfolios.

Securing profits

Avoiding further losses

Mitigating biases

Freeing up capital for new opportunities.

Now let’s explore each in turn:

Securing profits: A quick departure can help lock in gains already made, without the risk of riding what was a profitable investment all the way back down.

Avoiding further losses: Putting the brakes on deeper losses is one of the most significant advantages. Failure to do so can see relatively small losses quickly escalate.

Mitigating biases: Setting out a plan for dealing with underperforming assets makes an investor less susceptible to behavioural biases influencing decisions.

Freeing up capital for new opportunities: Exiting a position can release capital to invest in more promising ideas, improving overall portfolio flexibility and responsiveness.

Exit approaches of managers

We analysed 65,000 sell decisions across 180 portfolios to explore the approach of fund managers to exiting underperforming positions.

For each one, we captured the behaviour leading up to the final sell decision by comparing the performance between the previous investment call and the actual exit.

We also focussed on the quality of the timing by analysing the behaviours of the implemented strategies following the sell decision.

Purpose of sell decisions

Our analysis revealed 60% of sell decisions were executed at a loss. This suggests that selling is predominantly used as a damage control mechanism, rather than to realise profits.

On average, losses from losing trades significantly outweighed the gains from winning trades, with a win/loss ratio close to 80%. This means that when trades deteriorate, they often do so sharply. This is either due to high volatility or delays in recognising the underperformance.

We analysed how long it took managers to sell from the previous decision and found exit decisions were made three times as quickly when preceded by a ‘scale down’ call, as opposed to ‘buy’ or ‘scale up’.

This suggests that once a negative view has been initiated, managers are quicker to follow through with a move to cut the holding from the portfolio.

In contrast, when exiting a position that was originally bought or scaled up, managers tend to hesitate, possibly due to cognitive dissonance or reluctance to admit that an initial conviction was misplaced.

However, while these patterns highlight clear behavioural tendencies, it’s important to note that external constraints may also influence exit timing. Liquidity limitations, mandate restrictions and internal governance processes can all affect a manager’s decision to move out of a particular position.

While sell decisions are often made to reduce risk rather than to generate returns, only 15% of portfolios showed positive average performance on their sells. This suggests that opportunities to optimise exit timing—even for profitable trades—are often missed, and that a systematic review of sell-side behaviour could help enhance portfolio efficiency.

Effectiveness in taking profits

Approximately 40% of sell decisions are executed on winning trades, allowing managers to realise gains and lock in positive performance. This illustrates how sell decisions play an important role in profit-taking—but a closer examination into their timing and effectiveness suggests there’s room for improvement.

An important element is looking at the percentage of gains lost between the stock’s peak and the point at which an exit is confirmed.

We found that winning trades give back more than 50% of their peak gains before being sold, which highlights consistent challenges in timing exits – even when the strategies are profitable.

Despite identifying strong opportunities, hesitation or uncertainty about when to lock in gains can undermine profit capture.

The data points to a broader behavioural pattern where the fear of missing out on further upside may lead managers to hold positions beyond their optimal exit window. However, this can damage returns.

How they reduce losses

Our analysis showed that 55% of strategies tended to underperform after a sell decision, which confirms that managers are directionally correct—even if they are late to act.

This validates the function of selling as a loss-avoidance mechanism. However, managers take nearly twice as long to exit losing trades after they reach peak performance compared to winning trades.

We believe this is due to behavioural biases, such as anchoring performance expectations to a trade’s perceived peak, delaying exit decisions.

The faster exit timing following a scale down decision reinforces the idea that preparation for exit (via de-risking) facilitates faster and more effective decision-making.

Conversely, when no such signal exists, the decision to sell may be clouded by internal conflict, leading to delays and deeper losses.

These patterns underline the importance of proactive portfolio management. Managers who incorporate clear exit signals—such as de-risking steps or trigger thresholds—are better positioned to reduce losses effectively and act decisively when trades turn against them.

The different types of investor

As soon as an investment idea is initiated, a fund manager faces the ongoing dilemma of whether to maintain the position or explore more promising opportunities.

To illustrate this, we have likened the various approaches subsequently taken to the ways in which different athletes perform in their chosen discipline

The marathon runner : This manager is characterised by having a slow and steady exit speed. This highlights patience and maintaining a long-term outlook.

The sprinter: Exhibiting a brisk exit speed, this manager’s approach is more akin to a fast-paced run. They will look to capitalise on short-term market movements with agility.

The triathlete: This hybrid manager blends both styles. While initially moving at a swift pace, they will ease into a slower rhythm. This showcases their versatility and ability to adapt.

Each of these behavioural types comes with strengths and trade-offs. Recognising one’s natural tendency can help fund managers identify where exit behaviour may benefit from more structure or discipline.

The influence of behavioural biases

Our research confirms the presence of investment bias influences a manager’s decision when it comes to selling both winners and losers. Behavioural biases play a significant role in how fund managers make sell decisions, which can impact both profitable exits and the timing of loss-cutting. They can subtly distort judgment calls and lead to delays, premature exits from positions, or a general reluctance to act.

Some of the most common biases include:

Disposition effect

This means tending to sell winners too quickly and hold losers for too long. It often leads to premature profit-taking and delayed exits from losing trades, often locking in small gains and amplifying losses.

Confirmation bias

Managers favour information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs or strategies. This is a stance that can be hard to escape. Managers may ignore signs that a position is deteriorating, delaying exits due to misplaced conviction.

Overconfidence

Overconfidence can lead managers to falsely believe they have better information or skills. This can result in maintaining losing trades or exiting winning positions prematurely.

Loss aversion

This bias describes the tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains. It can lead to premature exits from positions that have the potential to recover.

Herd behaviour

Following the crowd can lead managers to make decisions based on the actions of their peers rather than their own analysis. This bias leads to delays exits as managers wait for group consensus, or triggers reactionary selling based on peer movements.

Endowment effect

This occurs when managers ascribe more value to the investments held than if they were to acquire them anew today. This bias can cause managers to stay with their holdings longer than warranted.

Case studies: how fund managers can avoid costly delays

The good news is that fund managers can avoid suffering deeper losses by having a better understanding of cognitive biases.

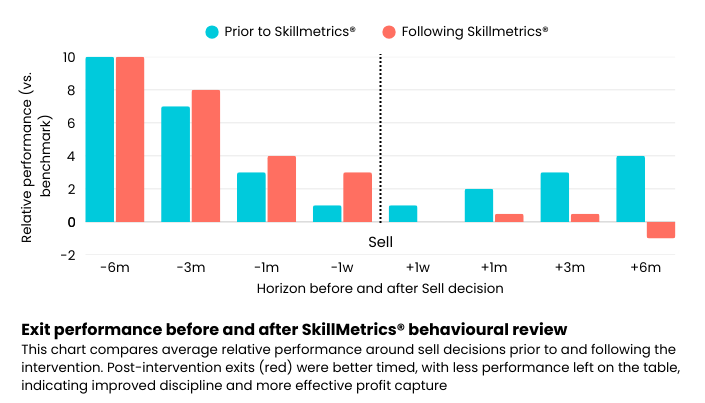

This is where SkillMetrics® has a valuable role to play. Our solution offers deep behavioural analysis that highlights the reasons for such delays. These insights can enable managers to change their approach and ensure sell decisions are guided by a clear exit strategy.

These two case studies illustrate how we have worked with managers to tackle such biases.

Case study one: unlocking missed upside

The first case study was a value-oriented US large cap equity manager that was performing well but wanted incremental improvements.

Our analysis revealed the manager was selling too early, particularly on profitable trades. On average, these outperformed by 4% over the following six months. We helped him deconstruct the drivers of his sell discipline and identified two financial parameters that were contributing to the premature exits.

A progressive adjustment process was introduced, with regular performance monitoring, to tackle these issues. Within a year, the manager’s sell profile had improved significantly, with less performance left on the table after exits. Combined with other changes made to the investment process, this led to an overall performance uplift of 2%.

Case study two: correcting disposition effect bias

Our second case study was a European equity manager with a very strong hit ratio who was being outperformed by peers. The problem was the losses incurred outweighed the gains. This meant his performance was positive – but also volatile and inconsistent.

We identified that the manager tended to sell winners early and hold losers for longer, which is typical of disposition effect bias. Internal review meetings were introduced to assess losing trades, which helped identify where obvious exit decisions were being delayed.

Volatility in performance subsequently dropped, enabling positive ideas to contribute more meaningfully. This resulted in a more resilient and consistent track record.

Conclusion

An effective exit strategy is a crucial tool for investors as it enables them to capture profits on winners, limit losses on underperformers, and free up capital for reallocation.

The key finding from our research is that portfolio managers often wait too long between recognising a position needs to be cut and actually pulling the trigger. These delays are often caused by behavioural biases, such as overconfidence and loss aversion, which can affect their response to changing situations.

Our conclusion is that managers can see returns improve by changing their approach and ensuring sell decisions are guided by a clear exit strategy.

If you’d like to explore how SkillMetrics® can support better sell decisions and behavioural insight within your investment process, we’d be happy to discuss.

About:

SkillMetrics® revolutionises investment expertise by providing advanced behavioural insights tailored for portfolio managers. Our cloud platform identifies strengths, weaknesses, and behavioural biases, leading to improved performance. CIOs/CEOs can coach teams to enhance results by focusing on the investment process. Fund Selectors benefit from skill monitoring and behavioural diversification.