Skill fitness: adjusting behaviour before it’s forced

Investment skill is usually only scrutinised after disappointing results. Periods of underperformance often trigger a full-scale examination of the process.

But this is too late. You can’t accurately assess a manager’s abilities after everything has gone wrong and they’ve been compelled to act. The focus should be on how they acted when the outcomes still looked acceptable. Were they willing – and able – to respond to changing dynamics?

In this article, we introduce the concept of skill fitness, discuss the role played by weak signals, and reveal what matters most to managers.

Main takeaways

Judgement comes too late: the timing of a fund manager’s

decision-making is no longer visible after performance failure.

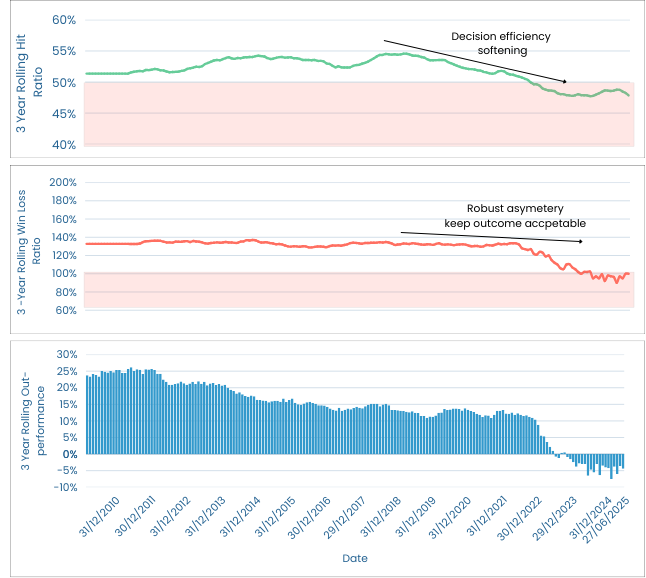

Failure is rarely sudden: outcomes can hold while efficiency erodes as deterioration typically unfolds gradually.

Timing reveals skill fitness: successful managers are willing to adjust behaviour adjusts when changes are optional rather than compulsory.

eak signals test judgement: they don’t compel action but reveal

whether behaviour moves under uncertainty.

When skill is judged too late

Fund managers find their investment philosophy and process coming under the most intense scrutiny when returns disappoint. Detailed reviews are carried out, exposure is reduced, activity slows dramatically, and risks are re-assessed. Everyone is demanding answers.

But this is actually the worst time to form a judgement. When an investment thesis collapses, previous behaviours will be rationalised, and narratives made plausible.

At this stage, it won’t be obvious when changes were made. For example, did exposure begin to unwind while the results still held, or after losses appeared?

Failure is rarely sudden

We looked at hundreds of portfolios and concluded that underperformance doesn’t happen overnight. Deterioration typically unfolds gradually. Conditions change, signals weaken, and the overall market environment appears generally less conducive and forgiving.

The difficulty is that performances can remain acceptable during such times. Past successes and diversification can help mask reality and enable inaction. But how a manager responds during these periods, where nothing is forcing change, can give us a valuable insight into their abilities. It’s where true skill fitness is revealed.

What is skill fitness?

Skill fitness is how responsive a fund manager is to the idea of changing their behaviour when such adjustments are still discretionary, rather than being forced upon them. It’s not necessarily about being right. It’s reacting to a changing environment before failure provides both the excuse and the justification to act. Behaviour can adjust quietly. Exposure will be trimmed, selectivity increased, and conviction expressed more cautiously, without any of them being demanded.

Of course, this isn’t always the case.

When there’s a sudden shock, behaviour and subsequent outcomes will move in tandem. In those cases, skill fitness is harder to gauge. But when deterioration unfolds gradually — which is how it usually happens — behaviour will happen first, and outcomes follow.

This is where weak signals come into play.

Where judgement is tested

The key to a manager’s success lies in their response to weak signals. These are the subtle signs that don’t compel action but test judgement. Weak signals are NOT early warnings. They don’t arrive with clarity, nor do they point to a course of action. A manager can justifiably ignore them.

However, what they provide is friction. A skilled manager will be willing to adjust their investment behaviour in response to an ever-so-slightly changing backdrop. Examples of weak signals include fewer decisions working as cleanly and winners requiring more risk to compensate for the less compelling.

Two decision-makers can spot the same signs and act differently, not due to having better information, but because they’re willing to respond without certainty. The distinction isn't whether early action is rewarded, but how exposure is managed as uncertainty rises. Small, reversible adjustments preserve flexibility.

While a degree of luck determines which path looks better in hindsight, behaviour determines how vulnerable the portfolio is to being unlucky.

When behaviour adapts…and when it doesn’t

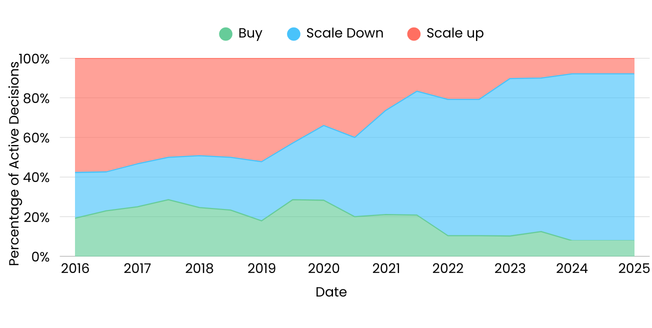

We have noticed a consistent pattern in decision-making histories. When conditions start weakening, responses fall into two distinct camps: adapt or rationalise.

In the first, posture changes quietly. Exposure is adjusted at the margin, and selectivity increases. Behaviour becomes more conditional as the environment becomes less forgiving.

In the second, behaviour remains largely unchanged. Positioning, activity, and conviction stay anchored to what has worked before. Early signs of deterioration may be noted but not acted upon.

Both responses can coexist with an acceptable performance. Both can be defended in real time. The difference boils down to timing. Behaviour adjusts while adjustment remains discretionary in the first example, whereas changes are made once discretion has narrowed in the second. This distinction is easy to overlook while results hold but it becomes decisive once conditions deteriorate further and the calls to act grow louder.

Example 1: quiet early adaptation

A manager operating in line with expectations sees conditions soften and volatility rise. Performance remains acceptable. Behaviour changes before anything forces it. New entries become rarer. Scaling up stops. Exposure is trimmed at the margin without signalling a change in view.

Nothing compels this shift. It happens while results still hold.

That early movement is visible.

Example 2: rationalisation through non-adaptation.

Decision efficiency begins to soften. Fewer positions work as cleanly as before, but larger winners continue to sustain overall results. Performance remains acceptable. Behaviour does not change. Position sizing, activity, and conviction remain steady. Early deterioration is noted but absorbed. Stable outcomes reduce any pressure to act.

Adjustment comes later, once results weaken, and the payoff structure no longer compensates. The delay is visible.

Conclusion

The way skill is assessed must change. The question most often asked after disappointment is still outcome-centred: What happened?

A more revealing alternative is: when did behaviour begin to change? This is where skill fitness becomes visible.

It’s not in the eventual decision to act — almost everyone will take this action eventually — but in the timing of that decision, relative to weak, ambiguous evidence. The standard changes quietly, but decisively.

Skill is no longer judged by how behaviour is defended after failure, but by how it evolved before failure and made any defence unnecessary.

About:

SkillMetrics® revolutionises investment expertise by providing advanced behavioural insights tailored for portfolio managers. Our cloud platform identifies strengths, weaknesses, and behavioural biases, leading to improved performance. CIOs/CEOs can coach teams to enhance results by focusing on the investment process. Fund Selectors benefit from skill monitoring and behavioural diversification.

SkillMetrics® gives investment teams a clearer lens on the behavioural dynamics that shape outcomes — particularly how conviction is formed, tested, and expressed under duress. If you want to strengthen your team’s behavioural edge in moments of market stress, let’s discuss.